Thinking Through Crisis in Latin America

Crisis, krisis, κρῐ́σῐς: as with many concepts rooted in Ancient Greece, exploring its etymology becomes an inevitable first step in understanding what this ubiquitous term signifies today. Both reassuring and potentially misleading, this search for a primal meaning features prominently in virtually any exploration of what the word “crisis” means—or encompasses—today. As a noun, the word has had legal, theological, and, more notably, medical usages validated by authorities such as Thucydides, Aristotle, Hippocrates, and Galen. Since its verbal root, krinein, can be translated as “to choose,” “to judge,” or “to decide,” the term’s meaning splits from the outset into what is ultimately the difference between a condition—a decisive moment—and the act of reaching a verdict.

Año nuevo aymara [Aymara New Year]. Tiwanaku, La Paz, Bolivia. 2024. Image taken by Annelí Aliaga. Copyright Annelí Aliaga, 2024

Crisis, krisis, κρῐ́σῐς: as with many concepts rooted in Ancient Greece, exploring its etymology becomes an inevitable first step in understanding what this ubiquitous term signifies today. Both reassuring and potentially misleading, this search for a primal meaning features prominently in virtually any exploration of what the word “crisis” means—or encompasses—today. As a noun, the word has had legal, theological, and, more notably, medical usages validated by authorities such as Thucydides, Aristotle, Hippocrates, and Galen. Since its verbal root, krinein, can be translated as “to choose,” “to judge,” or “to decide,” the term’s meaning splits from the outset into what is ultimately the difference between a condition—a decisive moment—and the act of reaching a verdict.

Reinhart Koselleck, the authority on the historical evolution of the concept, emphasizes that “in classical Greek . . . the separation into two domains of meaning—that of a ‘subjective critique’ and an ‘objective crisis’—was still covered by the same term” (“Crisis” 359). A critical moment and a critical choice have been intrinsically intertwined with the meaning of crisis since the term’s inception. Its medical meaning has remained relevant well beyond its Greco-Latin origins, highlighting, first, a specific relation between crisis and temporality and, second, the recurrent emphasis on two drastically divergent outcomes. Hence, a crisis was initially conceived as a transient state that represented a point of inflection, even if it proved relatively lengthy. In addition, its outcome was understood as either recovery or demise. This origin story is, in any case, a condensed version of the Hippocratic disquisitions, which have influenced Western thought for centuries. “From the seventeenth century on,” writes Koselleck, “crisis” was “used as a metaphor, expanded into politics, economics, history, and psychology” (“Crisis” 358). As expected, the term loses its clinical meaning in all its figurative deployments.

As it undergoes further metaphorical expansions—proliferating in academic titles, popular media, or becoming politicized and even weaponized— the word “crisis” comes to signify too many things and too vaguely. Crisis can be a synonym for “decay,” “deterioration,” “struggle,” “troubles,” “conflict,” or “predicaments.” There are “international crises,” “constitutional crises,” “housing crises,” or “identity crises.” We can discuss the “crisis of the humanities,” “the crisis in Main Street,” or speak, somewhat paradoxically, about “the crisis of critique.” Often, “crisis” becomes an empty signifier in the ever-overlapping languages of politics and the media: a placeholder, a buzzword, a rallying cry serving diverse and sometimes competing ideological agendas. At its worst, “crisis” can serve as a rhetorical device for reactionary politics or populist speechmaking. At its vilest, it becomes a tool for what Naomi Klein called disaster capitalism. Indeed, a hallmark of neoliberal strategy is the exploitation of crises to advance policies promoting deregulation, globalized commerce, and economic dominance while advocating market-driven solutions that benefit powerful economic actors, often at the expense of local economies or national sovereignty. In that sense, the geopolitics of “crisis thinking”—already present in its most influential analyses—becomes clearer.

From the 1770s onward, the term “crisis” emerged as a defining feature of Modernity, primarily viewed through a Western-centric lens. This view is evident in Koselleck’s seminal research, which traces the term’s usage in German, French, and English, focusing on events like the Austrian War of Succession, the French Revolution, and the American War of Independence. Koselleck draws upon the works of European intellectuals like Friedrich Schiller, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Denis Diderot, and Thomas Paine, further emphasizing the Eurocentric nature of crisis discourse. While thinkers such as Bruno Latour, Zygmunt Bauman, and Jacques Rancière have also helped illuminate the centrality of crisis to the project of Modernity, their narratives also situate this process within the Global North, where we find, so to speak, the crises that matter. This dominant framing calls for critically examining crises beyond these power centers, particularly in regions often marginalized by Western political and economic structures. The North/South divide becomes crucial in understanding the geopolitical disparities related to crisis thinking and representation, particularly in the context of humanitarian and environmental disasters. Devastating floods do not seem equally newsworthy whether they occur in Florida or South Asia; even fictitious disasters present their own hierarchy of pretend importance. We know that the catastrophic impact of climate change will be worse for the so-called developing countries and the Global South. We also know that our current environmental crisis will exacerbate poverty, force migration, and accelerate the detrimental effects of rapid urbanization. Yet the mainstream apocalyptic imagination in sci-fi films and novels tends to choose the centers of the world’s most powerful nations to stage the end of civilization.

In the face of such an imbalance in what we should consider the field of crisis studies, the intellectual—and perhaps moral—mandate would be to explore the charged geopolitical considerations surrounding the concept of crisis, examining how its understanding and application vary across different regions and power dynamics. In other words, the Western-centric bias in its historical analysis and the exploitation of crises for political and economic gains underscore the need for a more nuanced understanding that considers the diverse experiences and perspectives beyond the traditional Western framework. With the title Thinking through Crisis, this third edition of the LACIS REVIEW has accepted that intellectual mandate and offered the much-needed nuance and diversity. The essays collected here indeed provide a valuable and complex view of Latin America as a region grappling with multiple, intersecting crises.

A prominent theme across the articles is the impact of the climate crisis on Latin American communities, along with the various forms of response and resistance to it. Both Carlos Arenas and Nicole Bonino address the plight of the Guna people as climate refugees to discuss climate-induced migration. Arenas highlights the case of the ancestral Guna islands in Panama, which have become uninhabitable due to rising sea levels, forcing their relocation to the mainland. Focusing on the same indigenous community, Bonino explores how artists are using their work to document the experiences of climate refugees, advocate for sustainable changes, and challenge dominant narratives about the climate crisis through “eco-artivism”—a fusion of creative practices with environmental activism to raise awareness and inspire action. Lily Zander examines the devastating ecological crisis in Metztitlán, Mexico, highlighting the interconnectedness of climate change, neoliberal policies, and water scarcity and illustrating the importance of community-based solutions in confronting ecological crises. Concentrating on the Laguna de Salinas salt flat in Peru, Barbara Galindo Rodrigues analyzes the destructive impact of mining, an industrial practice that amounts to an eco-genocide against Indigenous communities and their ancestral lands.

Ligia González turns to one of the many migrant crises across the continent, as shaped by what she posits as competing “regimes of the gaze” where migrants’ first-person accounts on platforms like TikTok provide crucial agency to migrants, allowing them to construct their own images and challenge prevailing stereotypes. Pedro de Jesús González contrasts Western and Andean perspectives on catastrophe, invoking the Andean concept of pachacuti, a cyclical transformation process in which humans are not central but rather participants in a larger, interconnected cosmic order. Mental health is the crisis identified by Beatriz Botero as a silent epidemic in the region. In her piece, Botero argues for a comprehensive approach to improve mental health in Latin America that involves reducing stigma, increasing access to care, promoting conversations about mental well-being, and addressing underlying social and economic inequities. The crisis in higher education in Peru is the focal point of Fidel Revilla’s contribution, which offers a critique of the rise of for-profit universities, or “universidades bamba,” that prioritize profits over academic quality and have been accused of engaging in corrupt practices and neglecting investment in research and infrastructure. Alec Armon examines the Alliance for Progress, a U.S. initiative to counter communism in Latin America, focusing on its impact in Chile and the concerns of researchers at the University of Wisconsin’s Land Tenure Center about its limitations and contradictions, which failed to prevent the rise of Salvador Allende and the U.S.-backed coup.

The confluence between crisis and literature is also a recurrent theme in this issue. Oana Alexan Katz analyzes Reina María Rodríguez’s Otras cartas a Milena (2003), exploring how the book portrays the emotional, sensory, and bodily intensities of nostalgia within the context of Cuba’s post-Soviet economic, social, and political crisis. For Katz, Rodríguez’s writing becomes a form of resistance, expressing the “explosion” of individual subjectivity against the biopolitical control of the state, ultimately showcasing the limitations of language in representing the depth of this crisis. Rocío González-Espresati Clement examines the activist performance art of Guatemalan artist Regina José Galindo, exploring how the artist uses her own body as a medium to expose the systemic violence against women, forcing viewers to confront the brutality of the situations she depicts and compelling them to act against indifference to human rights violations.

Lyric poetry and photography also find a place in this multifaceted approach to crises in Latin America. The urban landscape of Mexico City, captured by German photographer Wilfried Raussert, and the poems by American poet Ann Fisher-Wirth merged into what the artists call “photopoems” to contest our everyday crisis of attention, of awareness, of life itself amid “piercing sci-fi landscape,” “construction that buried the sky” and melting buildings. The interconnected nature of the many crises explored in these essays resonates through this poetic and visual crisis thinking as well: a fitting colophon to the diverse and insightful analyses that precede it. The seasoned scholar, the budding academic, the activist, the poet, and the photographer meet in the following pages to offer a deeper understanding of the challenges confronting Latin America today while celebrating the resilience and resourcefulness of its people.

About the Guest Editor

Juan F. Egea is a Professor of Contemporary Spanish Literature and Culture at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of La poesía del nosotros: Jaime Gil de Biedma y la secuencia lírica moderna (Visor, 2004), Dark Laughter: Spanish Film, Comedy and the Nation (UW-Press, 2013) and Filmspanism: A Critical Companion to the Study of Spanish Film (Routledge, 2020). His forthcoming book is titled Visualizing Disaster: Crisis Photography in Contemporary Spain (McGill-Queen’s University Press).

References

Klein, Naomi. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Metropolitan Books, 2007.

Koselleck, Reinhart and Michaela W. Richter. “Crisis.” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 67, no. 2, 2006, pp. 357-400.

La dualidad del borde: navegando por los límites entre el Yo y el Otro

El borde más poderoso de todos se construye en la intrincada danza entre la figura materna y el recién nacido. Es ahí donde nacen los conceptos de “yo” y “otro”, donde las raíces y sus rizomas psíquicos se van conectando y desarrollando. Proceso que nunca termina.

Esta primera relación es una díada cerrada, simbiosis perfecta. Quien alimenta y quien recibe la nutrición son un solo cuerpo. El infante introyecta el cuerpo de la madre como parte de su narcisismo, la Totalidad. Sólo con un proceso gradual que se teje entre reconocimiento y diferenciación es que el infante puede entender la independencia y lograr un sentido de sí mismo. Este proceso de autodescubrimiento es lento y se nutre del reflejo y respuesta que hace la madre de las acciones y emociones del bebé. Esto da las bases para un emergente sentido de identidad y de seguridad; y muy importante: establece la capacidad de confiar.

Bajo el agua en Panamá, con unos peces y una estrella de mar al borde de la arena. Foto de Beatriz L. Botero. 2021.

El borde más poderoso de todos se construye en la intrincada danza entre la figura materna y el recién nacido. Es ahí donde nacen los conceptos de “yo” y “otro”, donde las raíces y sus rizomas psíquicos se van conectando y desarrollando¹ . Proceso que nunca termina.

Esta primera relación es una díada cerrada, simbiosis perfecta. Quien alimenta y quien recibe la nutrición son un solo cuerpo. El infante introyecta el cuerpo de la madre como parte de su narcisismo, la Totalidad. Sólo con un proceso gradual que se teje entre reconocimiento y diferenciación es que el infante puede entender la independencia y lograr un sentido de sí mismo. Este proceso de autodescubrimiento es lento y se nutre del reflejo y respuesta que hace la madre de las acciones y emociones del bebé. Esto da las bases para un emergente sentido de identidad y de seguridad; y muy importante: establece la capacidad de confiar.

El proceso pasa por el “estadio del espejo” descrito por Jaques Lacan: en este momento, el bebé se percibe delante del espejo, y la madre y el padre, con la sonrisa enigmática y su certitud de la distancia frente al bebé, es decir, desde sus propios pensamientos, sentimientos y deseos, ayuda a que se diferencie el infante y se entienda como individuo único.² Este distanciamiento permite forjar conexiones significativas con los demás.

El segundo borde fundamental para el funcionamiento del ser humano en la sociedad es el que separa la realidad de la ficción. Mientras dormimos todas las noches, durante los ciclos REM nos internamos en el mundo de los sueños. Es un universo con leyes propias como la “no contradicción” donde a nadie sorprende los disparates en donde la presencia de vivos y muertos o seres de distintos puntos del planeta pueden cohabitar en espacios improbables. Para que el adulto pueda entrar en este mundo paralelo al del mundo consciente, necesita ingresar a través de la imaginación y fantasía. En el infante tenemos el juego. El adulto puede llegar allí, por ejemplo, a través del arte. El artista, a diferencia del psicótico quien llega desde la enfermedad mental, puede entrar y salir a voluntad de su mundo imaginario y creativo.

El borde entre la realidad y la ficción se ha explorado en distintas direcciones desde la literatura y las artes. La distancia del triángulo que se forma entre la persona que escribe, la que lee y la narración que conecta el tercer ángulo, se debe entender como un borde en forma de franja, un espacio que habla de lo interno y lo externo. El arte barroco, por ejemplo, pone su énfasis en el flujo y el cambio, este miedo al vacío latente sugiere que las identidades no son fijas, sino que evolucionan. El barroco explica muy bien la inextricable relación entre Latinoamérica y sus representaciones artísticas. Para Alejo Carpentier, América es un continente en el que todavía no se ha establecido un “inventario completo de sus cosmogonías” cuando describe la importancia del barroco en el Realismo Mágico (mezcla entre lo maravilloso y lo real para Carpentier).

Para Albert Béguin, el romanticismo europeo -una forma renovada del barroco- habla de una Totalidad perdida a la que se debe aspirar. Para ello se requiere una disolución con la naturaleza. De ahí la importancia de cuidarla. Ambas formas artísticas desafían la rígida separación entre el “yo” y el “otro” y enfatizan la interconexión de todas las cosas en unión con el Todo.

Hay otros ámbitos en los que el borde entre el “yo” y el “otro” son importantes. En especial para las ideologías -construcciones imaginarias- en las que estamos inmersos como lo explica Harari en Sapiens. Entre ellas se destaca el ámbito político y las teorías postcoloniales que hablan de estructuras de poder jerarquizadas.

En el ámbito político, los conceptos de "yo" y "otro" se han utilizado para analizar las estructuras de poder y las dinámicas sociales, por ejemplo, cuando se piensa en las migraciones humanas, el “otro” a menudo se construye como lo opuesto al "yo", representando diferencia, desviación y amenaza. Esta construcción puede conducir a la marginación, la discriminación, e incluso la violencia, contra aquellos considerados "otros". David Gerber en su trabajo sobre migración retrata tres problemáticas que tienen que ver con el rechazo al “otro”: El Anti-extranjerismo, miedo a la escasez de trabajo para aquellos que ya están en una posición vulnerable, y la clase media y alta que quieren mantener el estatus quo de su bienestar. Este deseo de mantener lo ya existente, se puede observar en la teoría poscolonial, donde el término del “otro” ha sido usado para justificar las prácticas colonialistas, un lugar donde los colonizados son retratados como inferiores y necesitados de civilización por parte del colonizador. De manera similar, las académicas feministas han examinado cómo se ha utilizado el concepto del “otro” para subyugar a las mujeres, definiéndolas como distintas e inferiores a los hombres.

En el mundo contemporáneo, con la llegada de la inteligencia artificial (IA), las fronteras entre realidad y ficción se están volviendo cada vez más borrosas. Las tecnologías impulsadas por IA pueden crear simulaciones hiperrealistas y generar una idea falsa de realidad. La idea del multiverso con su enorme potencial tal vez permita una mirada más holística al ser humano.

Ante esta dicotomía, la filosofía apunta en otras direcciones. Filósofos como Emmanuel Levinas con la idea de “face” o Byung-Chul Han (sin ser considerados como cosmopolitanistas),³ junto con Martha Nussbaum y Kwame Anthony Appiah han desafiado esta visión estrecha del “yo” y del “otro” abogando por un enfoque que enfatiza nuestra humanidad y obligaciones morales compartidas. El cosmopolitanismo, en este sentido, exige el reconocimiento del valor fundamental y la dignidad de todos los individuos, independientemente de su origen cultural, creencias o identidad. Se declara una comunidad global donde los individuos no son categorizados en dicotomías entre el “yo” y el “otro”, sino que sean vistos como miembros interconectados de una humanidad compartida. Al abrazar ideales cosmopolitas, podemos ir más allá de las limitaciones del binario “yo”- “otro” y fomentar un mundo más justo y equitativo.

Estos conceptos, se deben evidenciar en todos los ámbitos posibles, pues puede abrirnos a una comprensión más amplia y matizada de nuestra relación con el “otro” y eso es precisamente lo que encontramos en este número de la revista LACIS REVIEW.

Hay grupos de personas que están interesados en mantener separados los conceptos de “yo” y “otro” como lo demuestra el artículo del trabajo colectivo de investigación liderado por Farías, en donde se estudia la manera en que la derecha en España y en Latinoamérica (caso específico del Perú) utiliza formas retóricas para prevenir a otros a que consideren las ideas feministas como importantes para la igualdad de género en estos países.

Otros trabajos por el contrario exploran los bordes desdibujándolos, entendiendo al “yo” en relación con los “otros” incluidos animales, plantas, formaciones geológicas espirituales, lagos, ríos. El universo indígena de México (Aruxes en Beilin), o en Bolivia la existencia de los ayllu como nos lo explica McNabb, o la Pacha como aparece en el texto de Guzmán. Hablan de la conectividad ente las partes con el Todo.

El mapa cuyos bordes estaban claros y delimitados en el papel, ofrece para los nuevos lectores, ya no un límite obtuso, sino que se espera que sea una franja, o como lo explica Anzaldúa, un tercer espacio donde las diferencias se interceptan, para que se pueda navegar en el borde natural. Este borde se descifra, ya no en el papel, sino dentro de una extensión de tierra: una franja, con sus biologías propias (Corzo). Quienes habitan en el borde del mapa, están en cierta medida abandonados de los gobiernos centralizados que dedican sus fuerzas a los problemas grandes de las metrópolis y dejan a las comunidades indígenas que habitan esas zonas limítrofes a su suerte, como lo explica el artículo de Chaparro exponiendo la precariedad propia del lugar y de las comunidades del borde.

En este mismo borde de mapa y control se encuentran las comunidades cimarronas como se lee en el artículo sobre el tema en República Dominicana (Leonardo), pero que cabría incluir cualquier espacio que invite a la libertad del ser humano. Este pasar el borde permite pensar en la experiencia del migrante, desde las categorías de “yo” y “otro” como lo podemos leer en la experiencia auto-etnográfica de personas que vienen de Puerto Rico (Bird-Soto) o México (Punguil), dando paso a la capacidad para tejer historias frente a la experiencia traumática. A través del tejido que habla de la memoria individual (Nelson) o grupal (Nace, Kallenborn) se puede fabricar la identidad. Nelson ejemplifica con su trabajo y el de otras tejedoras del mundo la importancia de honrar el pasado y Nace se pregunta la referencia al mercado y el consumo al utilizar tejido artesanal de comunidades marginales.

Si el espacio del mapa puede contener el espacio habitable, -como bien lo sabía Jorge Luis Borges- el tiempo también puede hacerlo: los clásicos griegos siguen estando presentes en las literaturas contemporáneas como lo explica Nelsestuen, traspasando el tiempo y el espacio a través del poder de la palabra. En el psicoanálisis lacaniano, como lo explica Marugán, la palabra enuncia al sujeto faltante pero nunca completa la ausencia.

En algunos textos de LACIS REVIEW, hay un reconectar con el borde difuso de la realidad y la ficción. Se vuelve a pensar la metaficción, o la metatextualidad, con géneros como el cine (Louie, Gonzalez, Martínez) donde el borde es en esencia un espacio de creación. La traducción, también atraviesa el borde del lenguaje pues intenta replicar con simetría el sentimiento, sin pensar solo en las palabras exactas de la literalidad y es lo que hace el acto de traducir poesía como aparece en el texto de DiPriete y Alegría.

Las palabras y las cosas también traen la simbología de nuestro tiempo, y aquí el trabajo de Brown, explica este borde desde la producción y el uso del tequila como puente entre culturas. Sabemos que el borde es necesario, porque en el mundo no puede haber dos cosas iguales, dice Sánchez Gumiel, cuando se acerca al análisis de la estética de Jorge Luis Borges -intuyendo el mundo virtual- y así nos hace ver el traspaso de este borde conocido en seres como Funes el Memorioso, o podríamos también decir de Johanes Dalhmann en El Sur o del mismo Pierre Menard y su Quijote o incluso los mismos objetos de Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis, Tertius que operan bajo leyes inconcebibles.

Esta tensión que contiene el borde también la podemos ver en escritos sobre literatura, específicamente en lo que Ruiz-Mautino denomina como un borde “Psico-simbólico” en la literatura realista de la escritora mexicana Luisa Josefina Hernández. Quien quiso romper los esquemas de la mujer fundada en la imagen católica de la Virgen María, pero también en las lágrimas de María Magdalena como lo muestra en su trabajo Pulla-Francia.

En los artículos de Shulemburg y Rojas se puede percibir un poco de optimismo por esta idea de borde entre el “yo” y el “otro”, cuando dice el primero que la literatura tiene poder para “estimular un ajuste de cuentas nacional colectivo en términos de navegar la frontera del odio y el perdón” y Rojas quien dice que es necesario “repensar las normas democráticas para fomentar la despolarización sin sofocar el cambio social. Necesitamos desarrollar sistemas de comunicación que aprovechen el poder de las comunicaciones en red sin ceder a la propaganda y la desinformación”, dando los ejemplos de consorcios de periodismo investigativo como Bellingcat.

En general, podría decir que este número de LACIS REVIEW destaca la naturaleza compleja y dinámica de la frontera entre el “yo” y el “otro”, enfatiza su fluidez y permeabilidad frente al mundo contemporáneo y nuestra comprensión cambiante de la identidad. Hoy día, se requiere un enfoque más matizado del concepto del “otro”, uno que reconozca nuestra humanidad compartida y la interconexión de todos los seres.

Le quiero agradecer muy especialmente al equipo editorial Jamie De Moya-cotter, Addison Nace, Diego Alegría, Andrea Guzmán, Anneli Aliaga y Avi Weinstein. A LACIS por su apoyo incondicional a las buenas ideas.

Nota: En esta edición intentamos ser flexibles al requerir una sola forma de citación (MLA, APA, Chicago), esto nos permitió admitir diferentes disciplinas y el uso de su propio formato.

¹ En el sentido de Deleuze y Guattari que son construcciones no lineales de redes que se entroncan en la cultura.

² Como Freud, Lacan, Piaget, Klein, Bowlby, Laplanche entre otros.

³ Chul Han critica algunas cosas de la globalidad como el consumismo y la pérdida de rituales.

Sobre la editora invitada

La profesora Beatriz L. Botero tiene un Doctorado en Literatura Hispanoamericana Contemporánea por la Universidad de Wisconsin-Madison y un Doctorado en Psicoanálisis en el que recibió Summa cum laude del Departamento de Psicología de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid España. Se especializa en novela latinoamericana, psicoanálisis y estudios culturales.

Es autora de Identidad Imaginada: Novelística Colombiana del Siglo XXI. (Pliegos Editores, 2020) y editora de Mujeres en la novela latinoamericana contemporánea. Psicoanálisis y Violencia de Género. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). La investigación de Botero pone especial énfasis en la identidad, el cuerpo y el conflicto social. También ha trabajado estos temas en relación con el arte visual contemporáneo.

Su última publicación académica fue “Novelas de violencia latinoamericanas: el dolor y la mirada de la narrativa”. The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Psychoanalysis, editado por Vera J. Camden, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2021,

Recientemente publicó Botero, B. L. (2023) Linterna, Luz radical: desde el dolor, el alivio y el consuelo. 4W-WIT Antología Bilingüe. Editorial Ultramarina. Sevilla, España.

Beatriz es la ganadora del Premio CLASP de Docencia Junior Faculty 2023

Para más información visite Professor Beatriz L. Botero (blbotero.wixsite.com)

Bibliografía

Appiah Kwame Anthony. Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. New York: Norton, 2006.

Béguin, Albert. El alma romántica y el sueño. Fondo de Cultura Económica México, 1996.

Borges, Jorge Luis. Ficciones. Madrid Alianza Editorial, 1997.

Bowlby, John. El apego y la pérdida. Buenos Aires Paidós, 2012.

Byung-Chul Han. The Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present. Cambridge Polity Press, 2020.

Carpentier, Alejo. El reino de este mundo. Madrid Alianza, 2003.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus. Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Freud, Sigmund. Tree Essays on Sexuality. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume VII. 1901-1905.

Gerber, David. American Immigration. Oxford. Oxford University Press, 2021.

Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: a Brief History of Humankind. New York Harper, 2015.

Klein, Melanie. Narrative of a Child Analysis: The Conduct of the Psychaoanalysis of Children as seen in the treatment of a ten-year-old boy. London: Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1975.

Laplanche, Jean. Nouveaux fondements pour la psychanalyse (New Foundations for Psychoanalysis), Paris, PUF, 1987.

Lévinas, Emmanuel. Ethics and Infinity. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1985.

Mahler , Margareth., Pine, F and Bergman The psychological birth of the human infant: Symbiosis and Individuation. Basic Books. 1968.

Nussbaum, Martha. The Cosmopolitan Tradition. Cambridge Harvard University Press, 2019.

Mead, George. Mind, Self and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1934.

Piaget, Jean, and Barbel Inhelder. The Psychology of the Child. Basic Books, 1972.

Edge Duality: Navigating the Boundaries Between “I” and “Other”

The most powerful border of all is built in the intricate dance between mother figure and newborn. This is where the concepts of “I” and “other” are born, where the roots and their psychic rhizomes connect and develop. Process that never ends.

This first relationship is a closed dyad, perfect symbiosis. The person who feeds and the person who receives nutrition are one body. The infant introjects the mother's body as part of the narcissism, the Totality. Only with a gradual process that weaves between recognition and differentiation can the infant understand independence and achieve a sense of self. This process of self-discovery is slow and is nourished by the mother's reflection and response to the baby's actions and emotions. This provides the basis for an emerging sense of identity and security; and very important: establishes the ability to trust.

Under the water in Panamá, with some fish and a starfish on the border of the sand. Photo by Beatriz L. Botero. 2021.

The most powerful border of all is built in the intricate dance between mother figure and newborn. This is where the concepts of “I” and “other” are born, where the roots and their psychic rhizomes connect and develop.¹ Process that never ends.

This first relationship is a closed dyad, perfect symbiosis. The person who feeds and the person who receives nutrition are one body. The infant introjects the mother's body as part of the narcissism, the Totality. Only with a gradual process that weaves between recognition and differentiation can the infant understand independence and achieve a sense of self. This process of self-discovery is slow and is nourished by the mother's reflection and response to the baby's actions and emotions. This provides the basis for an emerging sense of identity and security; and very important: establishes the ability to trust.

The process goes through the “mirror stage” described by Jacques Lacan: at this moment, the baby perceives itself in front of the mirror, and the mother and father, with the enigmatic smile and their certainty of distance in front of the baby, that is, from their own thoughts, feelings and desires, helps the infant differentiate and understand that is a unique individual.² This distancing allows for meaningful connections with others.

The second fundamental border for the functioning of human beings in society is the one that separates reality from fiction. While we sleep every night, during REM cycles we enter the world of dreams. It is a universe with its own laws such as “non-contradiction” where no one is surprised by the absurdities where the presence of the living and the dead or beings from different parts of the planet can cohabit in improbable spaces. For the adult to enter into this parallel world needs to use imagination and fantasy. In the infant we have play. The adult can get there, for example, through art. The artist, unlike the psychotic who can reach that universe from mental illness, can enter, and leave the imaginary and creative world at will.

The border between reality and fiction has been explored in different directions from literature and the arts. The distance of the triangle that is formed between the person who writes, the person who reads and the narrative that connects the third angle, must be understood as an edge in the form of a strip, a space that speaks of the internal and the external. Baroque art, for example, places its emphasis on flow and change; this fear of latent emptiness suggests that identities are not fixed, but evolve. The baroque explains very well the inextricable relationship between Latin America and its artistic representations. For Alejo Carpentier, America is a continent in which a “complete inventory of its cosmogonies” has not yet been established when he describes the importance of the baroque in Magical Realism (a mix between the wonderful and the real for Carpentier).

For Albert Béguin, European romanticism - a renewed form of the baroque - speaks of a lost of that Totality to which one must aspire. This requires a dissolution with nature. Hence the importance of taking care of it. Both art forms challenge the rigid separation between “I” and “other” and emphasize the interconnectedness of all things in union with the Whole.

There are other areas in which the border between the “I” and the “other” are important. Especially for the ideologies - imaginary constructions - in which we are immersed as Harari explains in Sapiens. Among them, the political sphere and postcolonial theories that speak of hierarchical power structures stand out.

In the political sphere, the concepts of "I" and "other" have been used to analyze power structures and social dynamics, for example, when thinking about human migrations, the "other" is often constructed as what opposite to the "I", representing difference, abnormality and threat. This construction can lead to marginalization, discrimination, and even violence against those considered "other." David Gerber in his work on migration portrays three problems that have to do with the rejection of the “other”: Anti-foreignerism, fear of job shortages for those who are already in a vulnerable position, and the middle class and high who want to maintain the status quo of their well-being. This desire to maintain what already exists can be seen in postcolonial theory, where the term “other” has been used to justify colonialist practices, a place where the colonized are portrayed as inferior and in need of civilization by the colonizer. Similarly, feminist scholars have examined how the concept of the “other” has been used to subjugate women, defining them as different from and inferior to men.

In the contemporary world, with the advent of artificial intelligence (AI), the boundaries between reality and fiction are becoming increasingly blurred. AI-powered technologies can create hyper-realistic simulations and create a false idea of reality. The idea of the multiverse with its enormous potential may allow a more holistic look at the human being.

With this dichotomy, philosophy points in other directions. Philosophers such as Emmanuel Levinas and the idea of “Face” or Byung-Chul Han (without being considered part of cosmopolitanism),³ along with Martha Nussbaum and Kwame Anthony Appiah have challenged this narrow view of the “I” and the “other” by advocating an approach that emphasizes our shared humanity and moral obligations -human beings are members of a single community-. Cosmopolitanism, in this sense, requires recognition of the fundamental value and dignity of all individuals, regardless of their cultural origin, beliefs or identity. A global community is declared where individuals are not categorized into dichotomies between “I” and “other,” but are seen as interconnected members of a shared humanity. By embracing cosmopolitan ideals, we can move beyond the limitations of the “I”-“other” binary and foster a more just and equitable world.

These concepts must be evidenced in all possible areas, as they can open us to a broader and more nuanced understanding of our relationship with the “other” and that is precisely what we find in this issue of the LACIS REVIEW magazine.

There are groups of people who are interested in keeping the concepts of “I” and “other” separate, as demonstrated by the article from the collective research work led by Farías, which studies the way in which the right in Spain and Latin America (specific case of Peru) uses rhetorical forms to warn others to consider feminist ideas as important for gender equality in these countries.

Other works, on the contrary, explore the edges by blurring them, understanding the “I” in relation to “others” including animals, plants, spiritual geological formations, lakes, rivers. The indigenous universe of Mexico (Aruxes in Beilin), or in Bolivia the existence of the ayllu as McNabb explains it to us, or the Pacha as it appears in Guzmán's text. They talk about the connectivity between the parts with the Whole.

The map whose edges were clear and delimited on the paper, offers new readers no longer an obtuse limit, but is expected to be a strip, or as Anzaldúa explains it, a third space where differences intersect, so that you can navigate on the natural edge. This edge is deciphered, no longer on paper, but within an extension of land: a strip, with its own biology (Corzo). Those who live on the edge of the map are, to a certain extent, abandoned by the centralized governments that dedicate their forces to the big problems of the metropolises and leave the indigenous communities that inhabit those areas to their fate, as Chaparro's article explain: exposing the precariousness of the place and the communities on the border.

On this same border of the map and control are the maroon communities, as read in the article on the subject in the Dominican Republic (Leonardo), but any space that invites human freedom could be included. This crossing the border allows us to think about the experience of the migrant, from the categories of “I” and “other” as we can read in the auto-ethnographic experience of people who come from Puerto Rico (Bird-Soto) or Mexico (Punguil), giving way to the ability to weave stories in the face of traumatic experience. Through the fabric that speaks of individual memory (Nelson) or group memory (Nace, Kallenborn) identity can be manufactured. Nelson exemplifies with his work and that of other weavers around the world the importance of honoring the past and Nace questions the reference to the market and consumption when using artisanal fabric from marginal communities.

If the space of the map can contain habitable space, - as Jorge Luis Borges knew well - time can also do so: the Greek classics continue to be present in contemporary literature as Nelsestuen explains, transcending time and space through the power of the word. In Lacanian psychoanalysis, as Marugán explains, the word enunciates the missing subject but never completes the absence.

In some texts in LACIS REVIEW, there is a reconnection with the diffuse border of reality and fiction. Metafiction, or metatextuality, is rethought with genres such as cinema (Louie, Gonzalez-Espresati Clement, Martínez) where the edge is essentially a space of creation. Translation also crosses the edge of language as it tries to replicate the feeling with symmetry, without thinking only about the exact words of literality and this is what the act of translating poetry does as it appears in the text of DiPriete and Alegría.

Words and things also bring the symbology of our time, and here Brown's work explains this edge from the production and use of tequila as a bridge between cultures. We know that the edge is necessary, because in the world no two things can be the same, says Sánchez Gumiel, when he approaches the analysis of the aesthetics of Jorge Luis Borges (intuiting the virtual world) and thus makes us see the transfer of this edge known in beings like Funes the Memorioso, or we could also say of Johanes Dalhmann in The South or of Pierre Menard himself and his Don Quixote or even the same objects of Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis, Tertius that operate under inconceivable laws.

We can also see this tension that the edge contains in writings about literature, specifically in what Ruiz-Mautino calls a “Psycho-symbolic” reality in the literature of the realistic Mexican writer Luisa Josefina Hernández. Who wanted to break the schemes of women founded on the Catholic image of the Virgin Mary, but also on the tears of Mary Magdalene as shown in her work Pulla-Francia.

In the articles by Shulemburg and Rojas you can perceive a bit of optimism about this idea of the border between the “I” and the “other”, when the former says that literature has the power to “stimulate a collective national reckoning in terms of navigating the frontier of hate and forgiveness” and Rojas who says that it is necessary “to rethink democratic norms to promote depolarization without stifling social change. We need to develop communication systems that harness the power of network communications without giving in to propaganda and misinformation,” giving the examples of investigative journalism consortia such as Bellingcat.

Overall, I could say that this issue of LACIS REVIEW highlights the complex and dynamic nature of the boundary between “I” and “other”, emphasizing its fluidity and permeability in the face of the contemporary world and our changing understanding of identity. Today, a more nuanced approach to the concept of the “other” is required, one that recognizes our shared humanity and the interconnectedness of all beings.

I want to especially thank the editorial team Jamie De Moya-cotter, Addison Nace, Diego Alegría, Andrea Guzmán, Anneli Aliaga and Avi Weinstein. To LACIS for its unconditional support of good ideas.

Note: In this edition we tried to be flexible when requiring a single form of citation (MLA, APA, Chicago), this allowed us to admit different disciplines and the use of their own formatting.

¹ In the sense of Deleuze and Guattari, which are non-linear constructions of networks that are rooted in culture.

² Like Freud, Lacan, Piaget, Klein, Bowlby, Laplanche among others.

³ Chul Han criticizes some things about globality such as consumerism and the loss of rituals.

About the Guest Editor

Professor Beatriz L. Botero has a PhD in Contemporary Hispanic American Literature from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a PhD in Psychoanalysis in which she received a Summa cum laude from the Department of Psychology at the Autonomous University of Madrid Spain. She specializes in Latin American novels, psychoanalysis and cultural studies. She is the author of Identidad Imaginada: Novelística Colombiana del Siglo XXI. (Pliegos Editores, 2020) and editor of Women in Contemporary Latin American Novels. Psychoanalysis and Gender Violence. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). Botero’s research places special emphasis on identity, the body, and social conflict. Also has worked on these issues in relation to contemporary visual art.

Her last academic publication was “Latin American Violence Novels: Pain and the Gaze of Narrative.” The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Psychoanalysis, edited by Vera J. Camden, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2021, pp. 128–144. Cambridge Companions to Literature.

She also published Botero, B. L. (2023) Linterna, Luz radical: desde el dolor, el alivio y el consuelo. 4W-WIT Antología Bilingüe. Editorial Ultramarina. Sevilla, España.

Beatriz is the winner of the 2023 CLASP Junior Faculty Teaching Award

For more information please visit Professor Beatriz L. Botero (blbotero.wixsite.com)

Bibliography

Appiah Kwame Anthony. Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. Norton, 2006.

Béguin, Albert. El alma romántica y el sueño. Fondo de Cultura Económica México, 1996.

Borges, Jorge Luis. Ficciones. Alianza Editorial,1997.

Bowlby, John. El apego y la pérdida. Paidós, 2012.

Byung-Chul Han. The Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present. Cambridge Polity Press, 2020.

Carpentier, Alejo. El reino de este mundo. Alianza, 2003.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus. Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.

Freud, Sigmund. Tree Essays on Sexuality. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume VII. 1901-1905.

Gerber, David. American Immigration. Oxford UP, 2021.

Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: a Brief History of Humankind. New York Harper, 2015.

Klein, Melanie. Narrative of a Child Analysis: The Conduct of the Psychaoanalysis of Children as seen in the treatment of a ten-year-old boy. Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1975.

Laplanche, Jean. Nouveaux fondements pour la psychanalyse (New Foundations for Psychoanalysis). PUF, 1987.

Lévinas, Emmanuel. Ethics and Infinity. Duquesne UP, 1985.

Mahler , Margareth., Pine, F and Bergman The psychological birth of the human infant: Symbiosis and Individuation. Basic Books. 1968.

Nussbaum, Martha. The Cosmopolitan Tradition. Harvard UP, 2019.

Mead, George. Mind, Self and Society. U of Chicago P, 1934.

Piaget, Jean, and Barbel Inhelder. The Psychology of the Child. Basic Books, 1972.

Why Transdisciplinarity?

The current socio-environmental crisis requires transdisciplinary research because the excessive disciplinary divisions may have contributed to it. The divisions between fields of knowledge—sciences focused on the natural realm, and humanities focused on politics and culture—prompted scientific progress, followed by economic expansion. But these divisions also led to a loss of wholistic ways of thinking able to respond to the complexity of real issues.

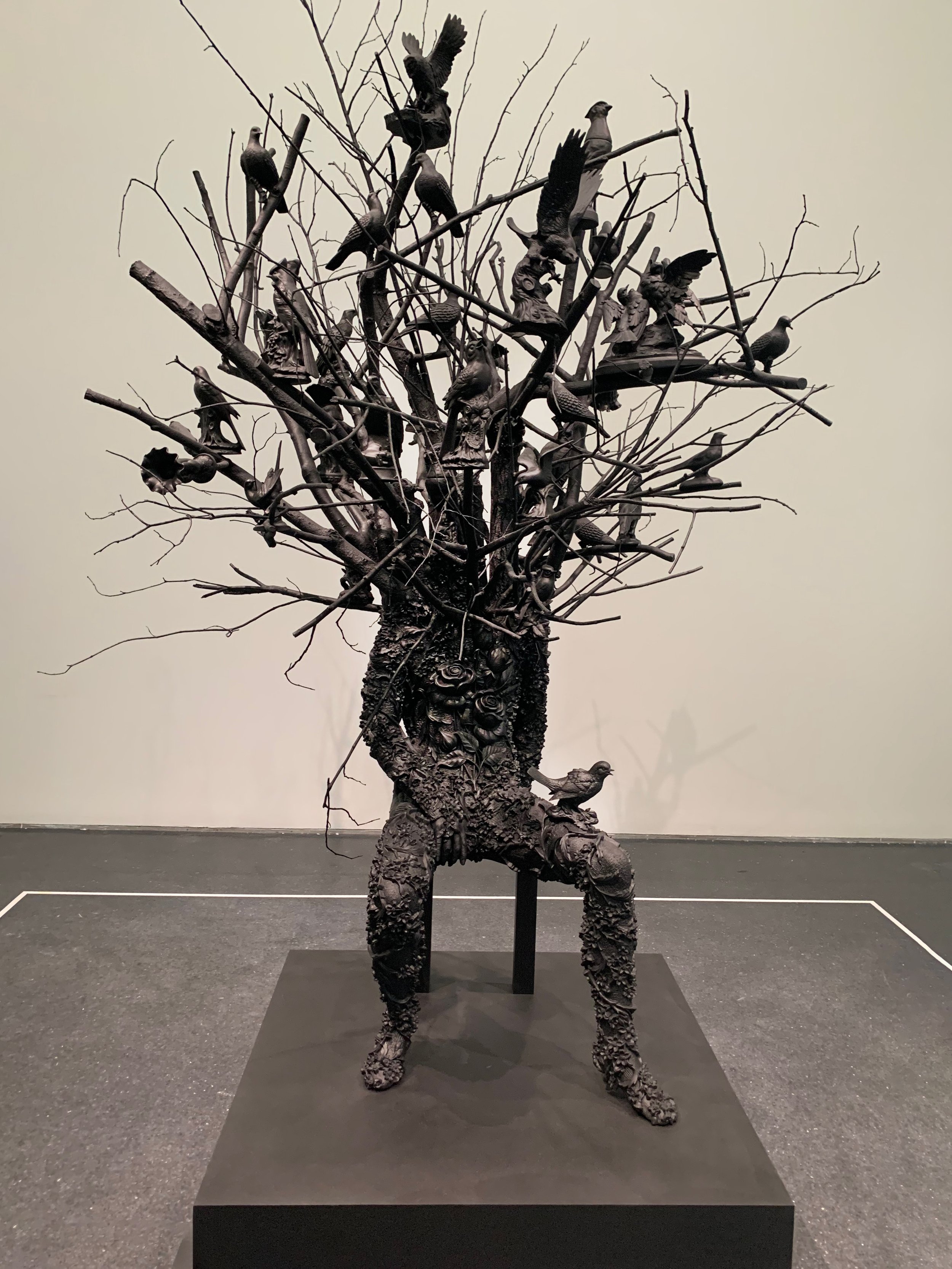

“Amalgam” by artist Nick Cave on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. Photo by Kata Beilin.

LACIS Review was conceived by a group of graduate students who took a LACIS seminar focused on Inter and Trans-disciplinary Latin American Studies between 2019 and 2021. It has not been easy to bring a new publication to life and we have done it slowly, but here it is. Welcome to the first issue!

This introductory issue contains 26 short essays, including two video talk presentations, in semi-formal style and presenting research projects that reach beyond the fields of their authors towards frameworks of other disciplines. These essays are authored by faculty and graduate students whose work focuses on Latin America and the Iberian Peninsula. The authors come from UW-Madison and from other campuses in the US. LACIS Review has invited publications in English, Spanish and Portuguese. In this first issue we read about various projects where science, technology, social studies, and humanities talk to each other to better understand “the big picture” of the multidimensional and un-disciplined reality of Latin America.

While in the common understanding, interdisciplinarity is defined broadly as research undertook in collaboration with more than one academic field, transdisciplinary research distinguishes itself by engagement with real, lived problems where multi-angled understanding is needed for strategic thinking. Transdisciplinary projects focus on how to better design and conserve multispecies systems of thought, life, matter, and technologies on our planet. It often involves collaborative work, including also non-academic actors and knowledges such as those of Indigenous people. As transdisciplinary research transcends the boundaries of disciplines, new transdisciplinary platforms emerge. Projects discussed in this issue can be placed, among others, in Environmental Humanities, Science and Technology Studies, Agroecology, Transdisciplinary Psychedelic Studies and New Materialities.

Latin American Studies have been interdisciplinary from the inception as they relied on dialogues between various fields of study to understand the complexity of ways of life and social structures in a historical and geographical context of the Luso-Hispanic World. At the beginning of the twentieth century, most research approaches were anthropological, archeological, and linguistic (Pakkasvirta, 2011). In the 1950s, under the influence of British cultural studies, Latin American Studies emerged as what today is called a transdiscipline; research focused on social, political, economic, and cultural problems lived by Latin American communities with an outlook for solutions. In the 1960s and 1970s, Latin American Studies focused on understandings of poverty. Dependency theory traced flows of resources from the periphery to the centers of consumption and analyzed extractivism as a function of colonization. Around the same time, Liberation Theology surfaced to condemn this dynamic as unethical. It produced rebellious political pedagogy and consciousness that became an important part of Latin American culture (Stenberg, 2006). This rebellious thought was reflected in Eduardo Galeano’s Las venas abiertas de América Latina (1970), the most widely read book of economic history in the Americas. Galeano transformed the concept of poverty into “impoverishment,” and questioned development promoted by European and North American institutions as imported and foreign to Latin American realities (Norget, 2007). These thoughts inspire today’s Latin American Studies to react to the intensification of extractivism in times of globalization and socio-environmental crisis (Escobar, 2011; Quijano, 2000; De Sousa Santos, 2015; Acosta, 2013, Otero, 2022; as well as Goldstein in this issue).

The current socio-environmental crisis requires transdisciplinary research because the excessive disciplinary divisions may have contributed to it. A science and technology scholar, Bruno Latour (2012), explains that while modern knowledge became disciplined, the universe has remained hybrid and undisciplined. The sculpture titled “Amalgam” by Nick Cave that accompany this introduction, where humans, birds, trees, and objects are all entangled in multiplicity of complex and disorderly relations, visualizes this undisciplined character of reality. The divisions between fields of knowledge, -- sciences focused on the natural realm, and humanities focused on politics and culture -- prompted scientific progress, followed by economic expansion. But these divisions also led to a loss of wholistic ways of thinking able to respond to the complexity of real issues.

In modern times, materiality and nature became an object of research of sciences. Natural objects made their way to the laboratory where they were dissected and analyzed. The imagination of nature as “out there,” separate from the cultured city, allowed the collapsing of life into sets of discrete, exploitable resources that enriched society through market exchanges. The compartmentalization of knowledge, and the emergence of disciplines allowed deep specialization essential for the technological and economic expansion. But specialists were often unaware of wide context of their narrow knowledges and could not address the complex side effects of application of these knowledges in technologies.

On the other hand, humanities detached from material reality and scientific knowledge, and western philosophers glorified the human mind’s capacity to transcend material limitations through imagination and beauty. The illusory character of this transcendence was revealed by the climate change. The Indian historian, Dipesh Chakrabarty (2009), of the University of Chicago, claims that climate change forces us to view this philosophy as a mistake because planetary collapse will mean an end to human freedom. Chakrabarty summons Humanities to return to Earth and deal with its problems. That means becoming truly interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary.

In the article that I wrote for the Forum of the Latin American Studies Association (LASA) this past summer 2022, I suggest that climate change and environmental destruction is not only the result of economic expansion, extraction, and destruction, but it can also be viewed as a result of the concepts and discourses that were used to justify extractivist economies and to turn blind eye to their effects. Narratives about progress, expansion, human exceptionalism, and work as struggle against nature were foundational for shaping the modern economy.

If the current socio-environmental crisis can be seen as a side effect of excessive divisions between disciplines and excessive specialization, transdisciplinarity deserves more attention in current academic education. Hispanic scholar and Associate Dean of Humanities at Rutgers, Jorge Marcone, shares the following reflection on the growing interest in transdisciplinarity on university campuses in the Americas:

I have been surprised by the enormous popularity and even a certain consensus, not only among researchers and students but also among authorities, of what has been known for a long time in studies of sustainability and social-ecological resilience by the name of transdisciplinarity. I understand that several definitions of this term circulate that, although they are not equivalent, intersect. On this occasion I am referring to a way of learning and solving problems, or of strengthening the capacity of agency to deal with them, which involves the cooperation of different sectors of society and university and research institutions to deal with complex challenges (Scholz 2020). The idea of the entrepreneurial University at the service of private industry, government agencies and even politicians in power is no longer the only current deciding university policies. In this conversation I have perceived a desire to promote and carry out research and teaching practices not only “for society” but “with society.” And this is pushing to transform the institution in different levels. (2022)

Marcone notes also that while all sciences recognize the need for greater cultural awareness, various humanities scholars doubt if they should be a part of projects focused on immediate benefits of nonacademic communities, and that there are institutional barriers for projects where distant disciplines, say microbiology and cultural studies, establish collaborations (yet, precisely at least one such project, “Microcosms” made it to LACIS Review!). Marcone notes that the emergence of environmental humanities prompts the awareness of the deep need for such projects.

In this LACIS Review, various essays exemplify transdisciplinary initiatives by connecting sciences and humanities and by recognizing that human minds and cultures are mediated by and entangled with plants, animals, and bacteria which are in turn carried by water and soil. Consequently, transdisciplinary understanding of human life, and economy leads us to questioning of separations between city and country, nature and culture established by modernity in contrast with indigenous and pre-modern conceptualizations. These alternative epistemologies are revisited today as we attempt to repair severed connections between us and the natural world. In this process important questions are asked: Is agency a uniquely human attribute? What is the role of materiality and of sciences in humanities’ education and research? How do humanities and social sciences contribute towards scientific work? Transdisciplinary thinking in this volume provides also a distanced meta-reflection about the planetary conditions of work itself, including academic work of those of us who research, write, and teach in the Academia, connecting and crossing borders between North and South. Finally, in various cases, research presented in this issue is centered on problems in ways that facilitate thinking about solutions of most pressing current problems such as poverty, climate change, perils of migration, racism, machismo, anthropocentrism, other forms of exclusion and injustice, and (mental) health. We hope you will enjoy learning about the exciting ideas of these essays that have been born at the border zones of different fields.

About the Guest Editor

Kata Beilin is a Professor at the Department of Spanish and Portuguese, and the past Faculty Director of LACIS, at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Kata specializes in Environmental Cultural Studies and promotes transdisciplinary and collaborative research across different fields, including non-academic partners. She is currently writing a book on Yucatec Mayas’ relationships with plants, forests, and bees as an important part of cultural revival and of the defense of Mayan land.

Works Cited

Acosta, Alberto. “Extractivism and Neoextractivism: Two Sides of the Same Curse.” In Beyond Development: Alternative Visions from Latin America, edited by Miriam Lang and Dunia Mokrani, Transnational Institute, 2013, pp. 61–86.

Alaimo, Stacy. Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self. Indiana University Press, 2010.

Beilin, Kata. “Climate Change as a Cultural Problem: Transdisciplinary Environmental Humanities and Latin American Studies” LASA Forum, Spring 2022. https://forum.lasaweb.org/past-issues/vol53-issue2.php

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. “The Climate of History: Four Theses.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 35, no. 2, 2009, pp. 197–222. https://doi.org/10.1086/596640.

Escobar, Arturo. Encountering development: The making and unmaking of the Third World. Vol. 1. Princeton University Press, 2011.

Galeano, Eduardo. Las venas abiertas de América Latina (1970). Siglo XXI, 2004.

Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Harvard University Press, 2012.

Marcone, Jorge. “Las humanidades ambientales y la transdisciplinaridad en la universidad.” LASA Forum, Spring 2022. https://forum.lasaweb.org/past-issues/vol53-issue2.php

Otero, Gerando. “Dependent development and Beyond; Can Latin America Transcend Extractivism?” LASA Forum, Fall 2021. https://forum.lasaweb.org/past-issues/vol52-issue4.php

Pakkasvirta, Jussi. “Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Latin American Studies.” Iberoamericana: Nordic Journal of Latin American Studies, vol. 40, no. 1–2, 2011, pp. 161–84.

Quijano, Anibal. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America.” Nepantla: Views from South, vol. 1, no. 3, 2000, pp. 533–80.

Sousa Santos, Boaventura, de. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. Routledge, 2015.

Stenberg, Shari J. “Liberation Theology and Liberatory Pedagogies: Renewing the Dialogue.” College English, vol. 68, no. 3, pp. 271–90, 2006. https://doi.org/25472152.