Measuring Agroecological Performance of Dairy Cattle Systems in the Peruvian Amazon

Abstract

Agriculture’s contribution to climate change and social injustice related food systems have become major societal concerns around the globe. However, there is increasing evidence that agroecological practices can contribute to improving the sustainability, resilience, and equity of agriculture and food systems. Using a recently released tool from the FAO, our specific goal was to assess the agroecological transition of smallholder dairy producers in the Peruvian Amazon. Our ultimate aim will be to explore the degree to which the agroecological transition contributes to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Silvopastoral system is an agroforestry practice that intentionally integrates trees, and pasture and forage crops into a single system for raising livestock. In our study, farms were classified based on grazing area covered by trees as either “silvopastoral” if more than 10% or “conventional” if less than 10%. Preliminary results indicated that farms classified as silvopastoral ranked high on an agroecological transition scale compared to conventional farms. This research will help Peru to document the multiple impacts of its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC under the Paris Agreement) which includes the implementation of silvopastoral systems in 119,000 hectares by 2030.

View of a corral where livestock are gather during the hottest hours of the day and given access to shade, water, and supplemental feed. This photo shows a small-holder farmer breaking apart blocks of salt used as feed supplements to provide minerals required by the young zebu-type (long droopy ears) livestock.

Illustration of Silvopostoral livestock system showing the three basic components of the system: the livestock, the pasture and the tree. This photo shows a calf sucking her mother cow in the shade of a tree while another cow is grazing the improved (seeded) pasture.

What is Agroecology and how do we measure Agroecological practices on farms?

Agroecology may be characterized as a set of farming practices, a social movement, or an emerging science (Wezel et al.). The term itself was coined in the mid-20th century from the merger of “agronomy” and “ecology.” At its origin, agroecology provided an approach to producing food from the land with less reliance on herbicides and pesticides and other environmentally damaging inputs associated with monocropping. In the last 20 years, however, the concept of agroecology has evolved from the field or plot scales to the farm and agroecosystem scales. Agroecology is now viewed by some as a promising approach to transition agriculture and food systems toward greater sustainability, resilience, and equity.

Reviews of sustainability assessment frameworks usually conclude that there is no one-size-fits-all solution (Schader et al.) and that the method that is most suitable to the context and the evaluation process should be selected. In 2018, the FAO was mandated to “...take the lead on developing methodologies and indicators to measure sustainability performance of agricultural and food systems beyond yield at landscape or farm level, based on the 10 Elements of Agroecology”. As a result, FAO coordinated the development of the Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation (TAPE) through a series of participatory workshops organized around the world. The aim of this tool is to produce consolidated evidence on the extent and intensity of the use of agroecological practices and the performance of agroecological systems across five dimensions: (i) environmental, (ii) social and cultural, (iii) economic, (iv) health and nutrition, and (v) governance.

TAPE includes four steps. Step 0 describes the main characteristics of the system and analyses the enabling environment. Step 1 consists of characterizing the agroecological transition of agricultural systems based on the 10 Elements of Agroecology. Step 2 assess the system based on 10 Core Criteria of Performance that have a direct link to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Finally, Step 3 consists of a participatory validation of the results.

Why using TAPE in dairy farms of the Peruvian Amazon?

Deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon has been substantial and continues to date. San Martin is the third region with the highest deforestation rate in Peru with 467,696 hectares of deforested forest between 2001-2020 (MINAM). Silvopastoral system is an agroforestry practice that intentionally integrates trees and pasture and forage crops into a single system for raising cattle. In our study, farms were classified as silvopastoral (Figure 1) if more than 10% of the grazing area was covered by trees or conventional (Figure 2) if less than 10%. TAPE was used to test the hypothesis that farms classified as silvopastoral ranked higher than conventional farms on agroecological transition scale. Data were collected on 22 farms between January and June 2022. Half of the farms were selected to be silvopastoral or conventional, but we also selected farms by size. Medium farms included 10 to 49 cattle heads and large, more than 49 cattle heads.

Figure 1. Silvopastoral system with trees arranged as live fences, and dispersed in the paddocks

Figure 2. Conventional system with trees arranged as live fences

What did we find?

The findings reported here focus on preliminary results of Step 0 and 1.

Step 0: Our study site is in the Northern Peruvian Tropics, in the district of Cuñumbuqui (San Martin Region, Figure 3). It has an area of 193,00 km² and a population of 4,681 inhabitants. The average altitude is 328 m.a.s.l. with temperatures ranging between 21-34 ºC. Dairy farming has been and remained one of the main local economic activities (Figure 4). The milk production is mostly for sale and a small part for self-consumption and the sale of milk is through intermediaries. Most of the farmers do the milking by hand once a day and the milk is collected every morning from each farm.

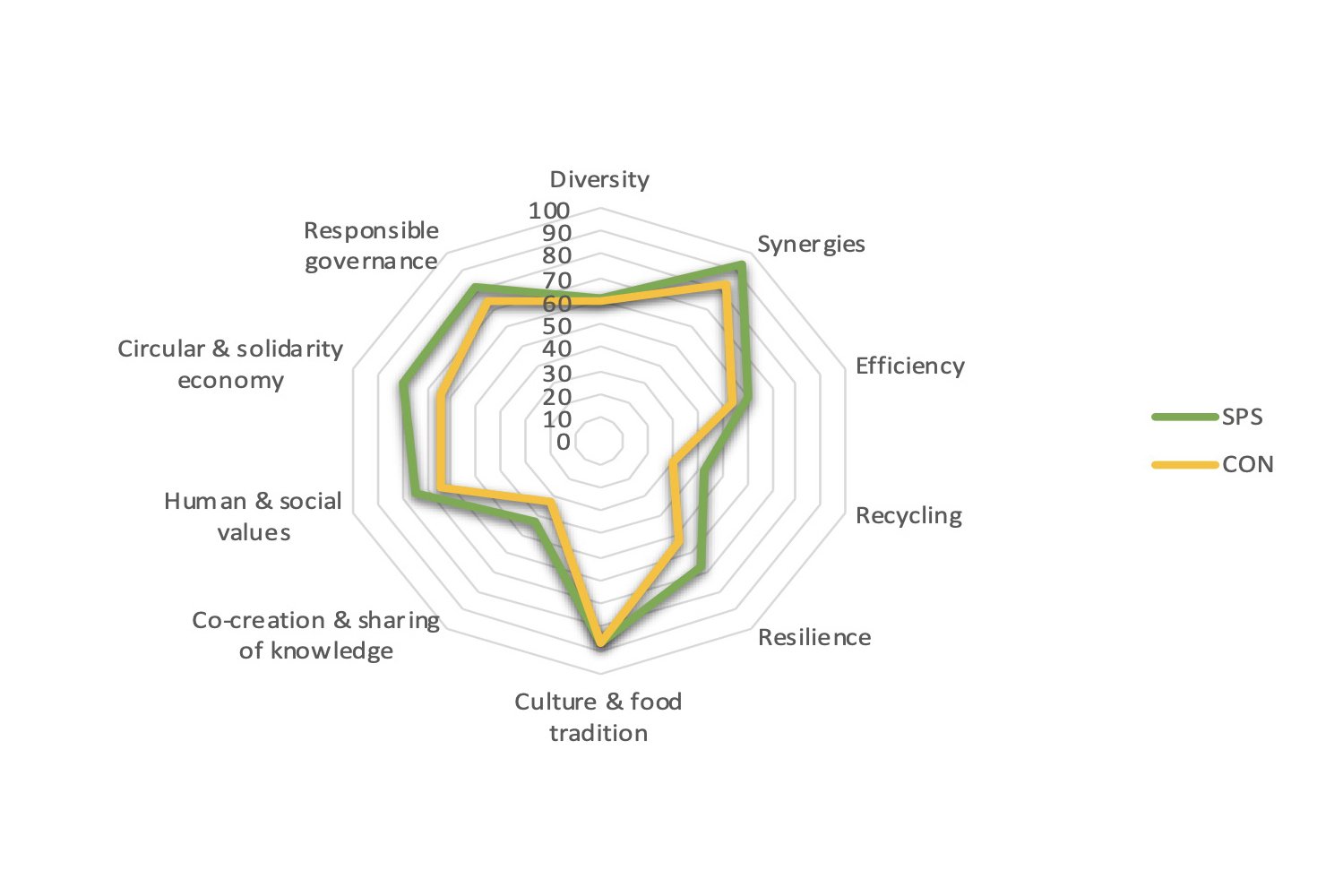

Step 1: The Characterization of Agroecological Transitions (CAET) is based on the 10 Elements of Agroecology. The first five elements (Diversity, Synergies, Efficiency, Recycling, and Resilience) are related to improving the current crop, animal, and farm practices, while the last five ones (Culture and food tradition, Co-creation and sharing of knowledge, Human and social values, Circular and solidarity economy, and Responsible governance) are more related to transforming the systems through its social dimension. Figure 5 compares the silvopastoral (SPS) and conventional (CON) systems for each of the 10 Elements of Agroecology. Overall, Synergies, and Culture & food tradition had the highest scores, while Recycling had the lowest score. Silvopastoral systems had significantly higher scores than conventional for Synergies, Resilience, and Circular and solidarity economy. Figure 6 shows the CAET scores of each farm. This score was calculated as the average of the scores of the 10 Elements of Agroecology. Although the highest-ranking farm on the CAET was a conventional farm, 8 of the top 10 farms were those classified as silvopastoral. Silvopastoral systems had a higher CAET score than conventional systems, in other words, they are closer to an agroecological transition than the conventional systems. Difference in CAET score between herd sizes were not found to be significant.

Figure 1. Location of Cuñumbuqui District

Figure 2. Main square of Cuñumbuqui District with the statue of a dairy cow showcasing the importance of dairy production to the region

What are our next steps?

Preliminary results of Step 1 indicated that farms classified as silvopastoral ranked high on an agroecological transition scale compared to conventional farms. However, data from Step 2 will be analyzed to rank the systems for their degree of alignment with indicators of selected SDGs. For example, we will evaluate secure land tenure, and soil health as two indicators of SDG 2 (Zero hunger), women’s empowerment as an indicator of SDG 5 (Gender equality), and youth employment opportunity as indicator of SDG 8 (Decent work and economic growth).

Figure 5. Radar graph of the 10 Elements of Agroecology

Figure 6. CAET results of the 22 farms surveyed

About the Authors

Dante Pizarro is a PhD student in Dairy Science. He obtained his DVM degree at Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (UPCH) and his MS degree in Animal Science at Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina (UNALM) in Lima, Peru. He is developing his research under the project “Improving sustainability and resilience of Peruvian Amazon systems through silvopastoralism” in collaboration with UNALM and the U.S. Dairy Forage Research Center.

Dr. Carlos Gomez is a Professor in Ruminant Nutrition at UNALM. He got his PhD in Animal Nutrition at University of Guelph (Canada). He has led research projects related to livestock production and its relationship with climate change in collaboration with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the International Potato Center (CIP), among others.

Dr. Michel Wattiaux earned his PhD in Dairy Science at UW-Madison where he is now a professor in Dairy Systems Management. Michel has extensive experience working with colleagues in Latin American, to study the contribution of dairy systems to poverty alleviation and sustainable agricultural practices as well as other Sustainable Development Goals. He has completed sabbaticals in Mexico and Costa Rica and has spoken on pedagogical issues in Costa Rica (EARTH University), Peru (UNALM) and Argentina.

Works Cited

FAO. TAPE: Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation. Process of Development and Guidelines for Application (test version). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2019.

MINAM. Geobosques. Programa Nacional de Conservación de Bosques para la Mitigación del Cambio Climático, 2022, https://geobosques.minam.gob.pe/geobosque/view/perdida.php.

Schader, Christian, et al. “Scope and precision of sustainability assessment approaches to food systems.” Ecology and Society, vol. 19, no. 3, 2014, p. 42, DOI: 10.5751/ES-06866-190342

Wezel, A., et al. “Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. A review.” Agronomy for sustainable development, vol. 29, no. 4, 2009, pp. 503–15. DOI: 10.1051/agro/2009004